Episode 1 – Bo Lanyon – A St Ives Legacy

21 October 2020 [22 min]

Bo Lanyon explores how artists working now have responded to the legacy of the St. Ives school in Cornwall, speaking with artists Lucy Stein, Hannah Murgatroyd and musician Gwenno about painting, the British Modernist tradition, ancient Cornish fougous, living with the dead and the lasting influence of his grandfather, Peter Lanyon.

Transcript: Please see at the end of the page.

What is a Fougou?

Wikipedia defines a fougou as ‘an underground, dry-stone structure found on Iron Age or Romano-British-defended settlement sites in Cornwall. The original purpose of a fougou is uncertain today. Colloquially called vugs, vows, foggos, giant holts, or fuggy holes in various dialects, fougous have similarities with souterrains or earth-houses of northern Europe and particularly Scotland, including Orkney. Fewer than 15 confirmed fogous have been found.’

You can read more about their locations, history and speculation on their uses in this BBC article.

In the podcast, Lucy Stein refers to two fougous in particular: Boliegh and Pendeen Vau.

What is Allantide?

Allantide (Nos Calan Gwaf) is more than simply a Cornish Halloween – watch this short film by the Cornish Culture Association to learn more about this Celtic festival.

Peter Lanyon (1918-1964) is described by Tate as ‘one of the most important artists to emerge in post-war Britain. Despite his early death at the age of forty-six he achieved a body of work that is amongst the most original and important reappraisals of modernism in painting to be found anywhere. Combining abstract values with radical ideas about landscape and the figure, Lanyon navigated a course from Constructivism through Abstract Expressionism to a style close to Pop.’

Chris Stephen’s book, Peter Lanyon: At the Edge of Landscape, was published in 2000 by David Bowie’s art publishing house, 21 Publishing.

In the podcast episode

-

Bo Lanyon

Bo Lanyon’s work explores an entangled landscape of experience. Influenced by both the history of expressionist painting & contemporary culture, paintings are built from layers of intense, gestural colour, as precise, illustrative elements hover in the foreground.

-

Hannah Murgatroyd

Hannah Murgatroyd is a painter whose work is underpinned by drawing and writing, shaping an open narrative of association.

-

Gwenno

Gwenno is a musician and conceptual artist from Cardiff, Wales. Her debut album, Y Dydd Olaf, won the Welsh Music Prize 2015 and Le Kov, her critically acclaimed second album, was written and sung entirely in Cornish. Le Kov translates as ‘Place of Memory’, and includes the song Tir ha Mor (land and sea) which was directly inspired by the work of Peter Lanyon.

Producer of the podcast episode

Supporter

Episode 1 – Bo Lanyon – A St Ives Legacy – Verbatim Podcast Transcript

Hannah Murgatroyd [00:00:00] You have to destroy your father or your mother, don’t you. And that’s what it’s about. You could love them, but you have to destroy them in order to be an artist. I just think you have to be critical of your gods you know.

Bo Lanyon [00:00:21] In the 1950s and 60s, the artists in St Ives, Cornwall, turned the seaside town into the hub of an art movement connected not just to London, but to Paris and New York and beyond. The achievements of these artists are embodied by the Tate St Ives building itself, where visitors can see the historical work side by side with the contemporary and the international. But it’s the lasting influence of these artists and of Cornwall itself that interests me here. These artists are recognisable names in British art history. Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Patrick Heron, Roger and Rose Hilton, Bernard Leach, Alfred Wallace, Naum Gabo, Terry Frost, Wilhemina Barns-Graham and Peter Lanyon. He is described by Chris Stephens in his book ‘Peter Lanyon: At The Edge of Landscape’ as one of the most exciting and original landscape painters of the 20th century. The only native born Cornishman of the St Ives artists, Lanyon’s representation of the land he grew up in was complex and passionate. For him, it was part social history, part myth, part aesthetic. A major collector of his work, David Bowie, said of his paintings that ‘the secret attraction, of course, is that through his landscape he revealed with assured and quiet complexity, the palimpsest of his own being’. I’m Bo Lanyon, one of Peter’s grandchildren and also an artist. So his influence for me is different. He’s there as an ancestor, in books, on walls and in family photos, a grandfather I’ve never met. But this isn’t about my relationship with him. I was curious about how that influence was now from Peter, St Ives, to Cornwall the place itself to see what the relationship with that history is for other artists working now.

Bo Lanyon [00:02:30] Lucy Stein is an artist, based in St Just, in Penwith, Cornwall. She has a major solo show coming up at Spike Island, Bristol, in May 2021. She’s married to the artist Stephen Claydon, and they have two young daughters. She’s known for her paintings of women, which utilise various techniques, including automatism and potato printing. Lucy sees her career so far as a meditation on suicide and sorcery.

Lucy Stein [00:02:58] The older generation are very kind of fixated on it. And younger people tend to be more, you know, to have more of a humorous, slightly sardonic, perhaps relation to it. But generally, it’s a proud heritage. You know, it’s a world class collection at Tate, and I think that’s such an important kind of thing. A rural place where you can have the benefits of being a kind of pastoral kind of environment, and then to have a world class collection that relates to that place is really unusual.

Bo Lanyon [00:03:37] Born in Bristol and raised on Dartmoor, Hannah Murgatroyd works between painting and drawing on a large and small scale. She had a solo presentation at Draw Art Fair in 2019 with Von Goetz and is a mentor on the Turps Painting School Correspondence Course. She set up the Painters Network Southwest in 2019 via Instagram, as a resource for painters to connect and instigate their own ideas. Both a thinking space for painters and those interested in painting with regular takeovers of the account and curated online shows in view of the pandemic.

Hannah Murgatroyd [00:04:12] It’s a tourist industry, isn’t it? But it’s also a cult, is also a kind of cult of middle class taste, and I think that’s a really dangerous thing for art. I think one of the reasons I’ve kind of disliked the St Ives painters and quite a lot of modern British painting is because of the derivative work that’s happened afterwards, which doesn’t have any of the kind of raw excitement in some of that early work. The cult is also that it’s kind of art for homes, not that art that shouldn’t be for homes, but it’s a bit like Kettle’s Yard. You know Kettle’s Yard St Ives, they’re these kind of palaces of middle class good taste. And yeah, that’s a dangerous thing for art.. The best art doesn’t really happen within those kind of parameters. The best art has frictions and difficulties, which is within some of those painters. Those original St Ives painters. But I also think that one of the things we don’t talk about is you know, they were incredibly middle class, if not well, they were upper middle class a lot of them. And you know choosing this kind of ascetic life, which is a very middle class thing to do to be ascetic, because you choose to have few possessions and have whitewashed walls and have these tasteful things all around you and the bits of driftwood, and then you kind of make Alfred Wallace into your God, because he’s the authentic being.

Lucy Stein (00:05:45) I think I’ve managed through quite a number of stages. My relation to this, to this history and the content that it generates for me. So currently I would say that I’m not in a particular kind of ironical relationship with it. I think I’m just not in that headspace at the moment. The great epic achievements of those people was really important to me for a while. Not so much any longer now I am just interested in the more formal stuff I would say. I mean, I was very obsessed with your grandfather. I mean, I still am very, very fascinated by his painting..

Bo Lanyon [00:06:27] Gwenno is a musician and conceptual artist from Cardiff, Wales. Her debut album won the Welsh Music Prize 2015, and Le Kov, her critically acclaimed second album was written and sung entirely in Cornish. Le Kov translates as ‘place of memory’ and includes the song Tir Ha Mor (land and sea) which was directly inspired by the work of Peter Lanyon.

Gwenno [00:06:52] I’d not paid a huge amount of attention to the St Ives School, in terms of the artists that had arrived in St Ives. But, I was then struck by your granddad’s work because I was like, oh, my goodness, this is the most progressive, freeing thing that I’ve seen. And, you know, I I came to his work late. And I was just overwhelmed by the freedom of it and the progressiveness of it and the boldness of it and the Cornishness of it. So it was just it hit on this thing that I was looking for in the Cornish identity. I was like, OK, so where is the freedom and the progression and the confidence? And it’s that it just hit me. I was just like, oh, my goodness, this is just incredible. And then I was looking into his life. And then his bardic name being Marghek an Gwyns ‘Rider of the Winds’. And then again and obviously it’s to do with him as an artist, in terms of how, you know, how much he wanted to push his practise. And also reading into his passion and feeling of wanting to defend Cornwall and go, no, you don’t quite understand. It’s actually like this. And I really loved that. And I loved that in his work. And so the song just came so easily then. And I was just sort of, just imagining him gliding over Cornwall, getting a better view and just that confidence, just like – whoosh – you know.

Music – 00:08:32 – Gwenno, ‘Tir Ha Mor’

Gwenno [00:09:13] It just gave me an approach to thinking about how to write the songs. And it gave me confidence in being as abstract as well sonically because we were really trying to do that because I was thinking a lot about his work. It’s the abstraction of it as well that I loved, because certainly from my background, Cornish Celtic identity could be more rigid in terms of visually, because up to that point I’d seen that sort of Celtic Cornwall with all the Celtic knots and all of that stuff. And then I’d seen, you know, these people that do these terrible paintings of the sea for people to put in Air BnB’s. And then I saw this and it was just like ah! Here it is.

Lucy Stein [00:10:11] My great grandfather, who is German, came to St Ives, St Merryn, over a hundred years ago, and they lived in London, but they bought land at Trevose Head, basically they came down, they bought land. And then some of them settled here, some of them stayed in London. When I was growing up, we’d always come and stay with Rick, my famous uncle and Jill and my cousins. And well first of all at Trevose Head at the house, they had called Redlands, and then in Trevose. And my grandmother had lived in Cornwall shortly before I was born. And my grandfather and his brother had sort of lived between Cornwall and London. There were people permanently and people here in the summer. My father spent a great deal of his youth down here, with his five siblings. And I mean, it was a bit it’s a bit of a sad history because his father committed suicide at Trevose Head. So there was a bit well, a lot of, sort of sadness around some of the history, but it was also somewhere that was very important to visit.

Hannah Murgatroyd [00:11:33] One of the things you asked me about was the influence of Dartmoor growing up. And we started to talk a little bit about Berlin as well and why I left Berlin. And one of the reasons for me was that I wanted to make landscape paintings as well. And even though I’m working with the figure, the landscape is very present in my work. And I found that in Berlin, the landscape is such a heavy place. If I thought about nature, if I went out in the woods or anything like that, I was essentially walking across very recent death. A landscape in Germany, for me, was never a space of liberty. It was really a space of weight and kind of reckoning. And that was one of my motivations for coming back to Britain. I needed to think about landscape painting. I needed to do that here on my home soil. And interestingly, since being in Bath, I’ve started to think about deeper layers within that. I think that there was kind of 2014, 2015, when I first started coming over to Bath, places like the Holburne had a very strong influence on me in terms of how I began to connect with the portrait, such as there is a big collection of miniatures. And also the Gainsborough portrait really influenced my thinking around the portrait. But more recently, I’ve started to kind of think deeper and theres the layers below the Regency and Georgian, which is kind of architectural and very much around the body as well. Below that then, there’s the Roman underpinnings of the city. And so I’ve been going and returning back to a lot of work I did 10 years ago, which was around mythology, Greek mythology, and particularly Aphrodite. And I think that that’s in part come from this kind of ancient layering within the city I’m in. I’m in a Roman city. And what that also means about that Roman city laid upon the primitive Britain below that, which is linked back to the Britain that I grew up in. It was very common for me to be around standing stones, to be around articles of faith without any known meaning, we have all our supposed and projected meanings around the constructions within the landscape. And the kind of history of body within that landscape is very, it is part invented. We have a sense of what we know, but we don’t actually know. We don’t have any total proof. And I think this kind of, this connection to landscape embodies, as something very, ancient and something connected to ideas of faith, but not necessarily organised religion.

Bo Lanyon [00:14:46] Peter Lanyon interviewed by Lionel Miskin, 1961.

Lionel Miskin (on audio clip) [00:14:51] And what about your roots and Cornwall and the kind of landscape and so on, which you keep harking back to. How important was this particular structural landscape to you when you developed into a mature painter sort of from ‘47 onwards?

Peter Lanyon (on audio clip) [00:15:09] Well I think very curiously, this country here and its stone and its oldness, were actually my own bones.

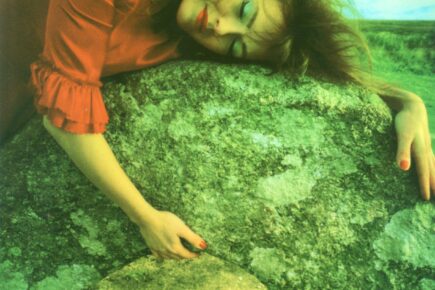

Lucy Stein [00:15:22] I was working a lot at this time with Simon Bayliss, he’s an artist who I actually met in Ireland on the West Coast of Ireland, in the Burren, which is quite a similar landscape to here. He was studying at an art school there and I was teaching there. And we really connected over a fascination with the sacred sites and would wander around the landscape conjecturing about these sites and what they might have been used for and so on. And the interesting thing for me was exploring the numinous properties of the two different Fougous. So Boleigh Fogou, it’s very different to Pendeen Vau, which is another fougou. And so, he was hypnotised in Pendeen and I was hypnotised in Boleigh. We’d already done these performance events, for example, Samhain at CAST. We’d already done that with some of the local Neo-Pagans from Penzance. We had this mad experience on Chapel Street in Penzance. The Raffidy Dumitz bands were practising and they were coming up the road behind us, going into all the shops and they were in their Samhain Allantide mode so there in this kind of really dark, eery, creepy, sort of steampunk, crow like outfits. We were going to the vintage shop and these people came in after us and they were playing this incredibly haunting song. And it was repeated over and over again. It was a dirge and it was actually their Cornish Allantide song. And it’s incredibly haunting and powerful. And it put me into a sort of trance. I was hypnotised by it basically. And then I went home and I had these boots lying around the house and I saw the boots as ravens and I knew something terrible had happened. I hadn’t checked my phone and when I went to check my phone I knew something awful had happened and my very close friend had died. So I kind of became really obsessed with the power of the local neo pagans or the Cornish penzance neo pagans. So when Theresa Gleadowe asked me to organise something at CAST, potentially for a seasonal changing event, I asked these people to come. I was basically put into a kind of trance for about a year after getting here. And it’s kind of like I felt like I was in this really specific space emotionally and you know it was palpable and I really wanted to drag everybody into the space with me. So it was a bit like entering the fougou.

Gwenno [00:18:21] Cornwall and Wales were Christianised, you know, in the Age of Saints. Which, you know, the English called the Dark Ages. So Christianity actually was there in, you know, the fifth century, whereas the whole of England was pagan. I’m really interested in early Celtic Christianity because I think it’s this really interesting bridge of spiritual revolution that has pulled in a lot of those pagan beliefs. Right at the heart of Christianity. And I think that that has had such a huge influence, really, on the Celtic identity and Cornish language identity as well.

Lucy Stein [00:18:58] I’ve just done some filming with my uncle, actually, and I’m not anxious about it particularly, but I’m certainly aware of the fact that particularly in Newlyn, there’s artists and fishermen coexisting, but it’s not there’s always a friction and friction is what makes it interesting. It’s not that we kind of understand each other but there is some kind of respect I think, But the worst thing would be if these kind of communities were not active, and, you know didn’t have any agency. They were like fake versions of artists and fake versions of fishermen. And then, and what would it be? I don’t know. I guess, you know, it’s interesting to be in a place that feels slightly combustible. And isn’t gentrified. But also you know, compared to other places I’ve lived it’s hard to kind of quantify how gentrification might happen down here.

Hannah Murgatroyd [00:20:07] Being a painter outside of London and knowing the kind of frustrations I was experiencing and when kind of connecting in to London and what was happening there. But also thinking there are so many painters around me who were disparate, and, there were some who were achieving things at a higher profile than others ,there are others just starting out. But there was no kind of way of people interconnecting. And I see a lot of graduates coming out and just kind of dissipating within the artist communities of the towns and cities and villages that we’re part of in the South West. But they were kind of getting lost in this. They could get up to London and get things happening there. And that there were a lot of painters here who have been going for a long time. Some have had, you know, lots of people’s with dips and the highs in their career. And I wanted to find a way of just bringing people together so that we could find a way for painters to support each other. I think this also came out of being in Bristol, which historically is not really, well, I mean, certainly in the last few years is not painting, has not figured as a presence. I mean, having my studio at Spike Island, if I’d say to anybody that was there, they’d be really surprised or say well there wasn’t any painting at Spike. And I think well, I know a lot of painters here and I’m meeting a lot of painters across the region. So why don’t we find a way to connect together and kind of if the institutions aren’t taking any notice of this, it’s also about, well you do something yourself? You don’t wait for somebody to take notice for you. Interestingly, in this last year, there’s suddenly been a kind of shift towards painting in the region as the Denzil Forrester is about to open at Spike, isn’t it? And then you’ve got Chantalle Joffe and Lucy Stein’s got her show there next year. And I think it was also, it was to counteract this St Ives imbalance that the idea of painting in the South West was about St Ives. And again, the kind of derivative school that comes with that.

Lucy Stein [00:22:18] So the show in Spike was postponed and I think it’s actually a good thing for me because it’s giving me more time and was gonna be a bit crazy because I had a baby at the beginning of March. And yeah, it was going to be only six weeks after that. But I had made all the works so it would have been fine, but now I’ve got another year to make more work and the whole thing takes more shape. Plus I’ve started this course in psychoanalysis, with a view towards maybe, probably doing the training. So I really kind of feel like the idea of extrapolation is really current to me, actually. And then such as to be able to go back into my own body of work and sort of like wrestle out the bits that actually mean something. And be quite confident about that. I think we were all traumatised now. And I think you know, it doesn’t have to be funny and it doesn’t have to be light. If I’m good at anything, I think I’m quite good at making things quite kind of emotional.

Peter Lanyon (on audio clip) [00:23:27] Beachcombing is a favourite activity of mine. And for me, the painter is a kind of beachcomber. I live in a country which has been changed by men over many centuries of civilisation. It’s impossible for me to make a painting which has no reference to the very powerful environments in which I live. I have to refer back continually to what is under my feet, to what is over my back and what I see in front of me. I am not interested in standing still in one position and I would use anything, bicycles, cars or aeroplanes to explore my relationship to my environment. My concern is not to produce pure shape or colour on the surface, but to charge and fill up every mark I make with information which comes directly from the world in which I live.

Bo Lanyon [00:24:29] In August 1964, Peter was on a training course with the Devon & Somerset Gliding Club near Honiton. As he came into land, caught in a crosswind, the glider flipped and crashed. Four days later, at Taunton hospital, he died. Peter’s reputation and influence has been reappraised in recent years from exhibitions such as Soaring Flight at the Courtauld Gallery in London and the publication of the catalogue raisonne by Toby Treves – a comprehensive study of all known works – to the BBC’s 2010 documentary “The Art of Cornwall”, with James Fox, which, although using a playful tone as we will now hear, introduced his work and approach to a wider public.

James Fox [00:25:18] Lanyon decided there was only one way to make a proper landscape painting. It was simple. You had to get out of doors, let go of your inhibitions and experience the countryside in every possible way. You have to get right to the edge of a cliff until you’re sick with vertigo. You’d have to get as close to nature as possible. Sometimes you have to get wet. You’d have to go rock climbing. You’d have to run up a hill and catch the view by surprise. Now, this all might seem a bit childish, but it’s central to Lanyon’s artistic philosophy, because Lanyon isn’t trying to paint what Cornwall looks like. He’s trying to paint what it feels like.

Gwenno [00:26:10] What interested me with Le Kov again was and it was the way that it was presented, I think, perhaps was more. There was a lot of information attached to it. As an artist, I feel lucky to have this language that I can explore that just I love the sound of the words. They work so well. You can really experiment with it. You know, that’s the use of it for me, an emotion exploring emotion that I haven’t explored before through lyrics and sound and singing. But it’s just music. And that’s the most important thing. And I feel I love the challenge of making music in a language that not a huge people understand. I find the joy in that something is understood without me having to explain. By creating those challenges to an audience, I think that that’s where the magic happens, that’s where the alchemy is in like, how an audience is interpreting it. And what it’s about. And I’d love to. I would love to reach a purity and expression where you’re not even gonna need to know, but you’ll know. You know, that would be the aim for me as a musician and a songwriter is that I really am trying to explore that with the album, is that can you know how I feel, the feeling I’m trying to get at here and I’m not going to explain, need to explain to you the details. Like, I think that’s a really exciting thing.

Lucy Stein [00:27:43] To coexist with the dead and the past is extremely complex. Many of the kind of legends from here, they were revealed to me in new light, just through talking to people, but also through reading the Dark Monarch or you know going to the St Ives archive. And I suppose, there’s a sort of gentrification that happens, isn’t there, with institutionalisation, and it’s quite easy to forget how complex and messy and sordid and difficult and overlapping and sensual all of these people in their lives were. You know it’s not benign or benevolent. And you know my own history with my grandfather and the effect that that kind of inherited trauma has on generations that didn’t even meet that protagonist are still deeply affected, perhaps, in an epigenetic kind of way by what happened to them and and the effects it has on other family members and that. You know, that’s interesting in many ways, but it’s interesting if you apply it to society of course and things that are being played out now relate to things that happened then. Maybe it’s more interesting to visualise yourself as this sort of parasite being hosted by these people. Or you know, or treat them as a kind of friendly ghost, as in the more ironical way of dealing with it, and then they get their own back on you eventually.

Bo Lanyon [00:29:25] During my conversation with Gwenno, I asked if there was anything she wanted to ask me. My answer serves for me as the right way to conclude, for now.

Gwenno [00:29:36] So how much of an influence has your granddad had on you, if any?

Bo Lanyon [00:29:41] I think that the most important thing to do as an artist is to find your own voice. And one of the most important things in doing that is it’s going to take time and it’s not going to come easy. And there’ll be times where that voice comes through louder and more clearer and others not so. And he’s an excellent influence in terms of just sheer drive, ambition, and I find it a wonderful thing to have if I’m at a low point kind of creatively. You know, I can kind of turn to his writings, perhaps, or I can just look at some of the work and it can almost be like a ghost on the shoulder, you know. And in a sense, like go on don’t worry, you know.

Gwenno [00:30:30] Ah nice so you really feel he’s with you?

Bo Lanyon [00:30:32] Yeah, sometimes, yes.

Gwenno [00:30:33] And he’s like come on Bo, you can do it. Go on!

Bo Lanyon [00:30:36] Yeah. I mean, that’s actually an incredibly personal thing to reveal. But yes, sometimes there is that sense of like a ‘Go on’, you know. But at other times you just have to kind of completely ignore it because it could actually be an unhelpful infiltration. So it’s a balancing act. But for the majority, it’s just, it’s a gift. It’s a treasure to have. You’re always in some way walking on the bones of your ancestors, aren’t you?

Bo Lanyon [00:31:08] Thanks to Martin Lanyon at the Lanyon Archive; Hannah Murgatroyd; Lucy Stein; Gwenno; Rosa Tyhurst and Carmen Julia at Spike Island; Heavenly Records; Downtown Music and Fiona Glyn-Jones.

END OF TRANSCRIPTION