Episode 4 – Ben Hartley – Ruderal

December 2020 [33.22 min]

In Episode 4, artist Ben Hartley explores the parallels between Ruderal plant species with the processes of gentrification & urban renewal. Focusing on a specific area of wasteland adjacent to Ben’s former studio and it’s anarchic flora, this podcast examines the seemingly inescapable link between artists and gentrification.

Transcript: Please see at the end of the page.

Ruderal species

Ruderals are plant species that colonise areas of land that have experienced a disturbance. The pioneer species are the most hardy, and are the very first to colonise a barren environment, such as an abandoned site or recently demolished building.

The word Ruderal, originates from the Latin “rubus”, meaning rubble. Ruderals can be interchangeably called weeds.

Ruderals are commonly found growing through cracks in the concrete, through gaps in walls, along fences and paths, or blanketing uneven and rubbish-strewn brownfield sites in urban areas.

-

Herb Robert

-

Broadleaf Plantain

-

Wall Barley

-

Horseweed

-

Hemp Agrimony

-

swipe left / right

scroll left / right

use your left / right arrow keys

scroll or use arrow keys left / right

Sean Roy Parker

Sean Roy Parker is an artist, environmentalist and cook based in London. His work examines the lifecycle of materials, complexities of civic responsibility, and problem-solving through collaboration. He practises analogue methodologies of craft and art-making, using leftover or abundant items of nature and artifice to explore feelings of eco-anxiety in late-stage capitalism, and redistribute resources through flexible care structures.

Recent projects include “Slow Yield” at Rupert, Lithuania (2020), “Changing our planet, changing our minds” at Wellcome Collection, London (2020), “Towards an Eco-Responsive Curriculum” at Haberdashers Academy, London with Freelands Foundation (2020), “Fermental Health” self-initiated, nomadic (ongoing).

Bedminster Green

“Occupying a prime site to the south of Bristol city centre, Bedminster Green lies between the vibrant East Street …. and the A38 / Malago Road …. Delivering Build-to-Rent apartments across two buildings, Bedminster Green features a mix of studio, one and two bedroom apartments with parking. Additional facilities will include: Amazon delivery, gym resident’s lounge and commercial space.” – Promotional text for Bedminster Green from Dandara Website

Stages

A: Hardy and well adapted to harsh and polluted environments with low quality soils, ruderals are integral in rehabilitating poor quality sediments.

1: Pioneering individuals such as creatives, artists and architects move into affordable or neglected neighbourhoods, or areas with available space for studios in urban areas. Current occupants remain and are unaffected by these developments.

______________________________________________________________________________

B: Plants native to an environment before a disruption may be forced out by opportunistic ruderals that thrive in low quality and compressed soil, cracks in the concrete or blocked drains, as they grow ever taller towards the sun.

2: As the area becomes identified as “up and coming” by Estate Agents through the increase in cultural capital by the local art scene. Estate agents begin to speculate on developments. Rent increases, forcing the original occupants out of the area, as more middle classes who can afford the living costs move in.

______________________________________________________________________________

C: With the successful colonisation of space after space Ruderals prevent the disturbed area from ever reverting back to the original state before the disturbance occurred. The natural state of the area is transformed forever.

3: Large numbers of properties are now getting gentrified and considerable numbers of middle class people are moving in. Non-residential buildings are now being converted to meet residential demand while long empty buildings held for speculation are put up for sale or developed. Small and specialised, often upmarket, shops and services pop up on high streets. As a result house prices and rents rise even further and more displacement takes place. Due to growing demand, and the increased cost of living the area, new areas of the city are identified and the gentrification process begins once again.

In the podcast episode

-

Ben Hartley

Ben Hartley is an eco-anxious artist based in Bristol. Concerned with the environmental impact of the art world and it’s obsession with material perfection. Believing perfection to be a wholly unsustainable concept, Ben believes the rejection of it constitutes a radical act.

-

Katie McClymont

Katie McClymont is the programme leader and senior lecturer for the MSc in Urban Planning and undergraduate programmes at the University of the West of England. Her research interests centre around planning theory, and its relationship with practice, values and community involvement in planning.

-

Henry Palmer

Henry Palmer is writer, comedian and activist born and bred in Bristol. Palmer is currently the Labour Party City Council candidate for Hotwells & Harbourside.

Producer of the podcast episode

Resources & Further Reading

Sarah Cowles (2017) Ruderal Aesthetics [http://www.ruderal.com/pdf/ruderalaesthetics.pdf]

Matthew Gandy (2013) Marginalia: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Urban Wastelands, Annals of the Association of American Geographers

The Bricks Podcast follows Bristol’s contemporary artists, on journeys within the city walls and beyond, along the leylines of the South West, up the A roads north, and through their unique observations on the world.

With thanks to Arts Council England and National Lottery players for funding this podcast series.

Episode 4 – Ben Hartley – Ruderal – Verbatim Podcast Transcription

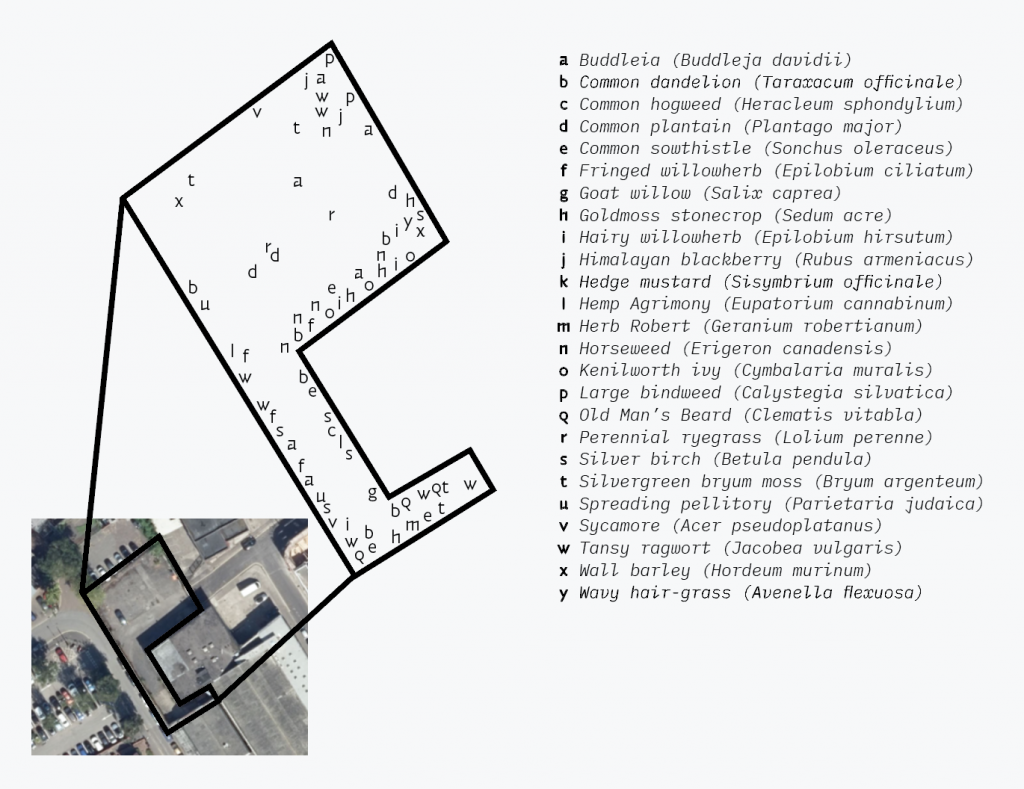

Ben Hartley [00:00:10] I’m currently standing in the wasteland space outside the formerly vacant industrial building on the street named ‘Little Paradise’ just behind East Street, in which my studio sits. A ‘meanwhile’ space earmarked for development, which is rented out to us artists before demolition. It is a square of broken tarmac and gravel, surrounded by a rather violent pointed black iron fence. Left untamed since the retreat of industry in the area, plants now push through every crack corner and gap in the tarmac and walls. They’re pretty much the same plants you see in any decaying or abandoned spaces in cities: ruderals or weeds.

Ruderals, originating from the Latin word Rubeus, meaning rubble, are plants that colonise areas of land that have experienced disturbance. Pioneer species that are the most hardy and are the very first to colonise a barren environment. Through the lens of my phone and an AI plant database app, I identify and document the flora that has turned this former industrial yard into an anarchic and impromptu garden. In the two years since the company moved out, the warehouse has been occupied by pioneering artists in need of space to create.

I’m Ben Hartley, an artist based in Bristol. As a young artist increasingly aware of the gentrification occurring in the area I live and work, I want to know just how involved I and other artists are in it, and if there’s any hope for us artists as a community. To me, ruderals have come to signify the cycles of urban regeneration and gentrification that inevitably involve artists and creative space: abandonment, the facilitation of creative space, inevitable displacement and development.

Sean Roy Parker [00:02:20] My name is Sean Roy Parker. I’m an artist, educator and cook based in south London. Thinking about ruderals as ‘experimental beings’ makes me feel incredibly warm to them on a physiological level. I feel kin with them. They look for potential life and potential opportunities in favourable conditions. Sounds like I’m sort of describing myself. They find new patches of earth, pulling out nitrogen, magnesium, phosphorus. They re-naturalise soil and collect more debris as it blows past and this in turn creates more hospitable environment for the less adaptable species. They attract wildlife: mostly pollinators like bees and butterflies, but also slugs, snails, flies, rodents who are looking for food and habitat.

The idea of ‘wildness’ is something that I’m super interested in. Our idea in the city of ‘wild’ is extremely sanitised and we need to embrace the chaos of unfettered weeds. Educate ourselves on culinary, medicinal and practical uses instead of dismissing them. We have a national case of ‘plant blindness’, especially moving through lockdown, when people were spending more isolated time outside. Thinking about projects like the lady in north London who has been, or I think it maybe started in Germany, where they’ve been drawing or writing the names of weeds and trees on the pavement in chalk. So, there’s this kind of sharing of resources and I like a new impetus to gain knowledge about non-native species.

Ben Hartley [00:04:30] There is nothing particularly remarkable about this space, it’s like any other urban wasteland across the country. But I find it here, now at the beginning of considerable changes, the warehouse and adjacent lands await demolition to make way for the coming development of 329 high rise homes for modern cosmopolitan urban inhabitants.

Robotic Voice [00:04:52] The new development of the up-and-coming Bedminster Green offer residents newly regenerated and fertile soils in room to expand.

We currently offer Buddleja, Buddleja davidii. Common Dandelion, Taraxacum officinale. Common hogweed, Heracleum sphondylium. Common Plantain, Plantago major. Common Sow Thistle, Sonchus Oleraceus. Fringed Willowherb, Epilobium ciliatum. Goat Willow, Salix Caprea. Goldmoss Stonecrop, Sedum Acre. Hairy Willow Herb, Epilobium Hirsutum. Himalayan BlackBerry, Rubus Armeniacus. Hedge mustard, Sisymbrium Officinale. Hemp-agrimony, Eupatorium Cannabinum. Herb Robert Geranium, Geranium Robertianum. Horseweed, Erigeron Canadensis. Kenilworth Ivy, Cymbalaria Muralis. Large Bindweed, Calystegia silvatic. Old man’s beard, Clematis Vitalba. Perennial Ryegrass, Lolium Perenne. Silver Birch, Betula Pendula. Silver Moss, Bryum Argenteum. Spreading Pellittory, Parietaria Judaica. Sycamore, Acer Pseudoplatanus. Tansy Ragwort, Jacobia Vulgaris. Wall Barley, Hordeum Marinum. And Wavy Hair Grass, Deschampsia Flexuosa.

What’s not to love about the exciting new growth at Bedminster Green! To find out more: go to your local Wasteland today! [Double Speed] Development may result in the destruction of natural environment. Developers are not responsible for any negative social, economic and ecological the development may have on local communities.

Sean Roy Parker [00:06:27] So artists are obviously an integral part of the gentrification process, where they move on from newly gentrified areas where they’ve been out-priced and then move on to lesser known neighbourhoods where it’s cheap and sometimes unfashionable. You’ve got this influx of predominately white art students, let’s say, and they can really overwhelm and overload the local ecology. There are usually some warehouses which become studio complexes. And this paves the way for sort of ‘culture vultures’ and speculative capitalists in the form of boutique restaurants, who proposed to feed the masses affordably, but end up attracting a lot of local tourism.

The cycle is complete when the ‘Big Lads’ move in. You know, supermarkets and chain restaurants. They compete with the small independent businesses and then basically the rent becomes too high for anyone to stay there. Also, to think about the small business owners, you know maybe the ‘early adopters’ in terms of the artists moving into the area, who are more maybe more adaptable than some of the existing businesses in that way, you know. They have their foot in the door with artists and they’re able, you know, they have like strong social media presence or wherever it is, and they’re much more flexible in terms of how they update and upgrade their business to fit with the times. So, in this way, you’ve got savvy, independent business owners that are almost like aspirational, in the sense of they are upwardly mobile, while pretending to care for and support local businesses who were existing there before. I find it’s really difficult to uncouple the two: artists and gentrifiers. Artists are a Litmus Paper, if you like. ‘Anti Capitalism’ becomes ‘aesthetic capitalism’.

I live in Lewisham which is in south London. It’s pretty urban, pretty grey. The streets look like they’re kind of regularly sprayed with glyphosate and I never notice much pavement vegetation, which is something that I normally look for whenever I’m outside. There are plenty of shrubby areas, but I think, to be honest, the council spends a lot of money keeping the pavements clear. I think it’s either a request from their constituents or has just become the norm. For me, this reinforces the nature/human dichotomy that Bram Büshner and Robert Fletcher described in their book The Conservation Revolution. Seeing humans as separate from nature, which disconnects us from our surroundings and creates commercial opportunities.

My favourite spot is down by the River in Brookmill park where the Ravensbourne shoots around the corner under a modernist train station. I often pick Alexanders, which are in my top edibles, and recently found some Water-mint, Winter-cress and some Bog-myrtle. There are a few more kind of unplanned spaces, like a car park opposite the shopping centre, which is home to a carpet of Lambs Tongue, Plantain and Dandelion. It’s got a low wooden barrier, so it’s less trodden on by the public. There’s also a spot in Deptford next to a train track, that has a lot of Sow Thistle. I really like the mature stems which are hollow and hexagonal and taste like a crisp iceberg lettuce leaf. It’s a very vivid memory of my childhood: my mum used to make me peanut butter and lettuce sandwiches, so I kind of swap out the letters for Sow Thistle.

Ben Hartley [00:10:50] Hardy and well adapted to harsh and polluted environments, with low quality soils, ruderals are integral in rehabilitating poor quality sediments.

When I first moved in, very little greenery had managed to force its way through the tarmac and gravel. As I am here today, just over a year later, many ruderal species have pushed their way through the now broken and washed-out surface of the previously busy industrial yard. Nature takes advantage of the relative quiet of the lockdown period and warm summer months to blanket the old stairs and tarmac with climbing Old Man’s Beard, Ivy and Mosses.

Saint Catherine’s place is an echoey shopping precinct that sits mostly vacant. Apart from a Farm Foods and an Iceland, that still retains its retro eighties signage, there is just a fruit stall and a marketing suite, which interestingly had also been an artist studio in a previous life. The accompanying show home tells the depiction of a sanitised and commodified urban experience. Wind picks up leaves and plastic bags as I walk through. Ruderals poke up through the cracks between paving slabs and grow in untamed planters beside the benches. It seems clear this area needs some kind of change. But is the kind of development that is coming and currently underway ultimately going to be good for local people? Or will it have increasingly negative impacts that push residents further and further out of the city score?

Katie McClymont [00:12:45] I’m Katie McClymont. I’m a senior lecturer in urban planning at UWE in Bristol: I lead the master’s course. I’m interested in questions of planning theory, which are questions about why we have a planning system—whose interests it serves. I am interested in community engagement and working with communities through my teaching, as well those concerns mainly around the sort of sense of over-development. So, there’s a lot of concern about the scale of the proposals for the Bedminster Green area: the heights of buildings, the densities of buildings and also that there was a lack of a sense of, maybe, a ‘Master Plan’ at that time.

There seemed to be lots of large-scale applications coming in, which will obviously have a very big impact on that area without necessarily a sense of coordination between them. Coordination between the new developments, coordination between the incoming developments and the existing residents, existing retail areas, existing green spaces. And a concern within that it was going to be very hard for people to have voices their voices heard. The people that were living in their area.

We make lots of judgments about people that participate in planning and make judgments about their motivations and whether people are being selfish or if people are trying to stand up for themselves and their communities. I don’t get a sense from anyone I talked to that they were trying to ‘gentrify’ the area. Many people I spoke to have been there for a while, but equally, the voices of people felt well-educated, quite well able to express themselves, which probably isn’t that surprising as they managed to organise a group and find an academic to talk to. So, I just think there’s maybe some questions there about who we’re seeing, those people, but also who those people are that are speaking. Do they think they’re speaking for themselves: ‘And I like my view’ or ‘I like my area as it is’. Or are they speaking to wider concerns about the quality of development coming into an area. And I think it’s difficult, and it’s difficult for me as an external observer, to put those judgments onto people’s motivations.

I think planning is very helpful in this and planning in a way which thinks about things such as the need for social infrastructure. So: schools, doctors, open spaces, social spaces. And ensures that they’re not sort of an ‘add on’ at the end of a development—the development is something that genuinely listens to some of the concerns around what people feel is problem with some of the proposals here. And I think it’s that again, it is still about the scale, also about the scale of affordability and affordable housing within these proposed developments—which seem very low. Seems to be that the Bristol City Council has lowered its expectations and they’ve been lowered again in the developments. So that’s problematic: what’s being built there, if it’s not actually homes for a range of people? It’s a very paradoxical question. Something that I have had few conversations with others are that interested in this on is about: how do you do public consultation for public that isn’t there yet, if you’re looking at large scale new developments? I suppose that is again, listening to some of the people that are there already, thinking about whose voices are not part of the process and thinking about the way that development can be socially beneficial and brought together more holistically.

There’s lots of examples from Germany and the Netherlands of large-scale redevelopment being master planned, in a way that allows space for things such as self-build housing, more genuinely affordable housing being built through Co-Ops and other such organisations. Because you’ve got land assembled on a large scale; because the private sector has a clear and defined role and the ability to make money and profit from the land. But not in the way that it’s quite often done in this country, in this context, which is the exclusion of other developments.

I’ve not come across it anyone explicitly saying, as a developer: they hired a load of artists and stuck them into some warehouse so they can sell the land for more money. I think this whole debate ends up slightly putting the blame on artists, for what’s really about the property market and property market speculation. And… artists will go to places that the space to create in an affordable space and that adds to the vibrancy of our cities, towns, wherever else that this happens. There maybe needs to be, in some of the debate around planning and land value capture, a sense about how you can adequately tax the profits on development, that accounts for things such as that. Rather than as a developer, you just scoop up things. Whether that’s a good school in a neighbourhood: ‘Oh yes, our land value is now worth so much more, because those teachers were working really hard!’ or ‘Oh! They put in a nice new train station, therefore our land…’.

So how do you equalise some of those sorts of, the gains that one party gets because of what another party is doing? And maybe around art and artists is a sense of having a broader ‘meanwhile’ use strategy in a city. Ensuring there’s always a certain amount of space available at very low cost for artists wherever that is. Ensuring the artists are consulted when new cultural spaces or new community spaces are being built, in a way that is useful and meaningful for creative practises, as well as just providing a sort of ‘Village Hall’ style building, where you can have a kid’s party in, but maybe that is not so good for anything else. That says: why do things around social infrastructure, in development? If you’re provided with the nice council designed set of floor space: is that what you really want or need? It depends on who you are and what is that you’re trying to do in that space.

I think, the city as a space to be creative, is of value itself and we need to be better as planners. I think players are not terribly good, at actually talking about the values of places and spaces, which aren’t for work or housing or something really obvious, intangible and more off the mainstream of ideas. They’re not shops; they’re not schools; they’re not houses and offices spaces; they’re spaces that can hold more than one value, one use at a time.

Ben Hartley [00:20:05] Plants native to an environment before disruption may be forced out by opportunistic ruderals that thrive in low quality and compressed soil, cracks in the concrete or block drains, as they grow ever taller towards the sun. Among the many ruderal plants I came across in the wasteland, I didn’t find any more numerous than small dotted growths of Plantago Major: the broadleaf plantain. Not in any way related to the plantain of the banana family, Plantago Major is a small flowering and stringy leaf plan that thrives in compressed and disturbed soils, making it an excellent polliniser of urban spaces. But it also has another name known by Native Americans at the time of European colonisation: White Man’s Footprint. Named such, because it thrived in the compressed soils and damaged ecosystems that grew around the invasive colonial settlements. The ability of the Plantain to withstand frequent trampling, makes it vital in the process of soil rehabilitation of Brownfield and urban wasteland spaces, in order to facilitate the conditions for further ruderals to move in.

Henry Palmer [00:21:30] My name is Henry Palmer, and I wrote a book about the gentrification of Bristol: Voices of Bristol: Gentrification and Us.

So, growing up in my part of Whitehall, which was opposite Chelsea Park (the ever-notorious park back in the day) around the corner from City Academy school, was a mixture of good and bad. It was good insofar as it’s being cosmopolitan and diverse. I grew up next to Jamaicans, Indians, Africans, which installed in me, and I think everybody around that area, an acceptance of other cultures.

But there were negatives as well. The European Commission in 1998 classed our ward of Easton, which that part of Whitehall was a part of, as one of the most deprived wards in the whole of the South West of England, and this was true to my experience. What do we find with more deprived areas? We find higher levels of crime, higher levels of substance abuse. My experience was being threatened with a gun on a cycle path, being beat up numerous times in the area, threats…

When I came back from University in 2016—I studied philosophy and film studies down in Kent Uni—something that was really quite telling for me was, as I was working as an Uber driver for a year, was that I would speak to two tiers of people, if you like, who could be judged based on the response that they give, when I’d say that I was from Easton. In that they’d either respond: ‘Oh, show us your bullet wounds’ or ‘Oh nice!’. And it was this latter response, which was really telling and shocking to me, because I’d never ever heard Easton described as nice before.

So, this is really explained by gentrification, which if you don’t know, is effectively the migration of a higher social economic group into a traditionally lower socio-economic area. Why? Because it’s closer to town or um, you know, what you generally find, is people move to these inner-city areas because they’re cheaper there’s more amenities, more opportunities and this is what happened in Easton and is happening right now.

So, you know, there’s more bars around now, sort of, spirit bars and things like that—which we never experienced. You know, our version, if you like, fifteen to twenty years ago, was an unsuccessful builders pub. In terms of house prices in the late nineties, the average house price around there was about three, four times average income; now it’s more it’s more around the area of ten to fourteen times. So, there’s definitely been a change. And Whitehall, Easton is one of the areas which is being gentrified.

Ben Hartley [00:24:27] With the successful colonisation of space, ruderals prevent the disturbed area from ever reverting back to the original state, before the disturbance occurred. The natural state of the area is transformed forever. East Street is an interesting and diverse mix of people, buildings, businesses and sounds. Despite there being increasingly more shuttered shops there appears to be a strong sense of community. Side roads that had connected to East Street before the pedestrianisation, are now cut off by colourfully graffitied and regenerated wheelie bin planters, from which various local, ruderal grasses and shrubs grow. Flanked by slick wooden benches, in an overtly obvious attempt at beautification, it is a sanitised appropriation of ruderal aesthetics present in graffiti covered underpasses and skate parks.

I’m now standing in the empty warehouse where my studio used to be. The maze-like plasterboard walls that had previously divided the echoe-y metal arched hallway into individual studios, are now gone. Aside from general clutter lining the walls, the floor is bare. The planning permission for the development has been given the go-ahead: meaning the demolition is imminent.

Henry Palmer [00:25:57] There will be fewer Bristolian accents. House prices will continue to surge. The locals who have been there for generations, will be pushed further South and a new culture will develop. I think the way things are going to be very difficult to sustain to or to stop it now. I think, as it goes further South, gentrification, when it comes down to places like Hartcliffe. And it be really interesting to see, as urbanisation spreads further South like it did in London fifty, seventy years ago, how those communities react. Because they’re bloody strong, strong council estate communities. It should be really interesting.

One of the main pillars of the South Bristol gentrification’s representative institutions buildings is the Tobacco Factory. What George Ferguson did in the 1990s in purchasing that and enabling it as a bar, as a Theatre, necessarily was going to appeal to higher social economic groups. Although Shakespeare was for audiences where 80% of the audience couldn’t read and write, that’s not the case now, right? It necessarily appeals to higher economic groups and I think that explains why places like North Street have been more quick to gentrify than places like East Street.

I understand the negative consequences of gentrification in two terms really: economic consequences and cultural consequences. I think the economic financial consequences are worse. That is, being priced out, you know. Not being able to afford to rent. Examples of cultural consequences are things like, so the local poet Lawrence Hill, from Saint Pauls, a cultural consequence that he spoke about is the ‘cultural clash’, if you like. He was born and bred here, is about fifty years old, but was made to feel as though he’s a threat, through the gentrifiers reaction to him. That is, when they see him in the street—he’s a mixed heritage, Jamaican Bristolian—and he’s visibly seeing them check their wallet when he’s walking down the street.

So, the financial consequences is the housing crisis: housing being unaffordable, unaffordable rent; unaffordable purchase prices. In the late nineties again, it was something like three to four times annual income to buy a house, now it’s up to fourteen times. And that’s been exasperated by, effectively 40 years of neoliberal, conservative policies. Libertarian policy started with Margaret Thatcher in 1980 with the ‘Right to Buy’ policy which enabled council tenants to buy their council property. They could before, but it was it was seldom really granted.

So, since 1980, we’ve seen a huge shortage in the stock of council houses that the state owns. It was 33% council housing in Bristol in 1980. Now it’s 13% and if we’re good to go off national trends about 42% of those will belong to buy-to-let landlords. One of the big consequences of this or big issues with this, is that none of the money that was made was allowed to be reinvested into council properties. So, the ‘Right to Buy’ policy needs to be reversed and retracted. Council houses need to be bought; a land value tax needs to be brought in. Currently, council tax is based on old fashioned, antiquated 1990s stats. Right now, a developer can hold onto land and not be deterred from just sitting on it.

If you bring in a land tax it deters that, if you bring in a rent cap—We had a rent cap actually up until 1957. I believe renters in California actually, between the years 1994 to 2010, through a rent cap saved something like 2.2 billion dollars. Collective ownership: The Exchange is a great example of a bar-pub which is collectively owned by about 450 different people in Old Market. The fact that it’s collectively owned, means that it’s never liable to be bought up by private developers who want to extort it for, you know, affecting property for profit at the expense of people. Abolish buy-to-let mortgages—just this really preposterous policy that came in the late 1990s, which effectively says ‘Do you want to make money from owning things? Here you go.’ It’s not a sustainable solution. Immanuel Kant speaks about something being ‘just’ and ‘moral’ insofar as it’s in line with the ‘rule of universality’. In other words, if not everybody can do it, then it’s not just.

Ben Hartley [00:31:13] Searching for a new, old warehouse to facilitate an affordable and accessible creative space, the only available buildings within that range of affordability are located in similarly, de-industrialising neighbourhoods, further out from the city’s core. This movement begins the cycle once again. With this action, repeated a thousand times, development, population displacement, gentrification, the city grows ever outwards—like a thorny tendril of the wasteland-growing Bramble, reaching out for space and light. As these anthropogenic disturbances of urbanisation irreversibly alter the natural environment, the whole earth itself becomes a ruderal landscape.

Huge thank you to Sean Roy Parker, Katie McClymont and Henry Palmer for their time and contribution. Big thank you to Jack Gibbon and Jessica Akerman from Bricks and producer Rowan Bishop for all the production support.

Outro Voice [00:32:20] This podcast was brought to you by Bricks. Bricks brings together the people of Bristol, through collaborative art projects, public realm producing, community led Co-design and securing the spaces our communities need to thrive. On our site you will also find the blog posts with links and images related to the subjects covered in this episode, and profiles of all our artists and projects. So go check it out. BrickBristol.org.

END OF TRANSCRIPT.