Episode 10 – Kayle Brandon – Our Plant Neighbours

July 2022, 25 mins

This podcast explores the development of a new work of Kayle’s in Stoke Gifford, Bristol, where she worked with local residents and herbalist Chris Roe to produce an edible food mapping plaque.

The project explored the current abundance of local native food species surrounding the new neighbourhood, and captures a moment in time of natural space on the edge of future development.

Transcript: Please see at the end of the page.

Episode by

-

Kayle Brandon

Kayle Brandon is an inter-disciplinary artist, who works within public and social contexts.

Co-producer

TRANSCRIPT

Rowan Bishop 00:04

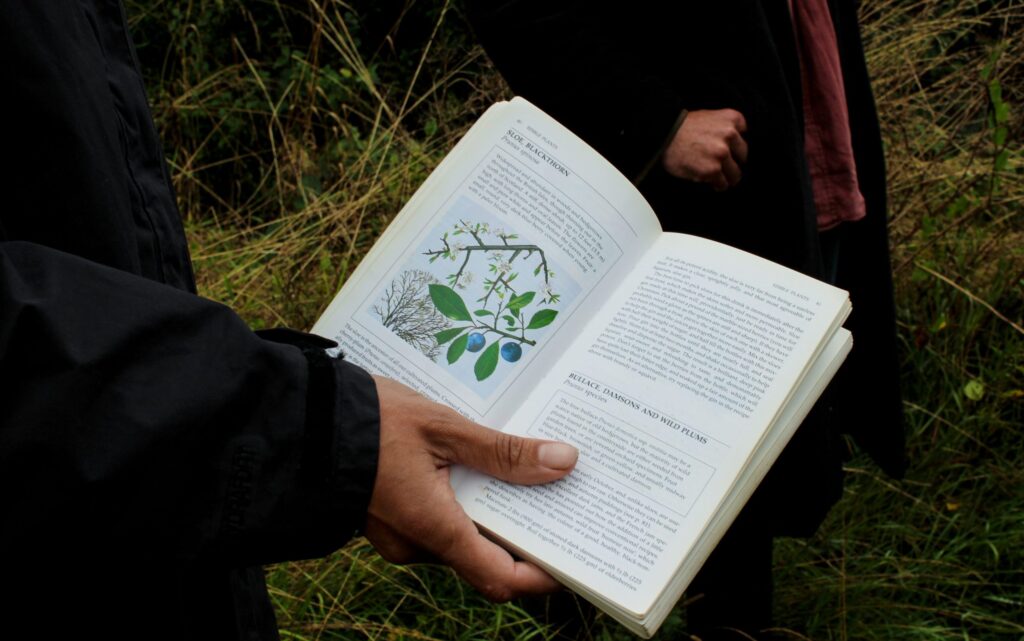

Kayle Brandon is an interdisciplinary artist making works which are embedded in specific sites, places and communities, with a particular focus on people’s relationships to nature, urban spaces, animals, architecture and survival. In 2021 Bricks commissioned Kayle to deliver a public art programme for new housing development at Roseneath Gardens, Stoke Gifford in South Gloucestershire. Local residents joined Kayle and herbalist Chris Roe on a series of neighbourhood creative explorations and workshops. Participants mapped the edible and medicinal plants living in the surrounding areas and learned about their uses. These explorations and workshops influenced a new tree planting plan and the creation of a local food map brass plaque, which was then installed in the local park. Residents and visitors can take rubbings from the plaque to help them explore the native food species in the area for generations to come. In this episode, we’ll hear Kayle talking about her practice and about the Roseneath project. We’ll also hear from Teresa Hazelwood, a landscape architect who talked to us about the process of planning the green infrastructure on new developments and the practical challenges of delivering spaces that take into account resident’s needs, planning and environmental laws, as well as the local ecology of a site. Also, throughout the episode, we’ll hear residents’ voices recorded on site at Roseneath during the workshops

Kayle Brandon 01:27

I’m very interested in nature. I always have been. So as a sort of life work thread, it sort of encompasses all of it – all of my interests from a child onwards, really. I’m really interested how the city provides space or what actually the city has taken space from nature, right, from the forest, from the fields, from the earth. And even from the skylines, you know, constantly imposing upon it in an urban context. But I’m interested in how Bristol in particular acts in some ways as a kind of, a diversity, place of nature, and non human entities and human entities intermingled. Early on in my practice, when I was collaborating a lot with Heath Bunting and Kate Rich, and Graham Hogg, and these all kind of Cube people met them through the Cube cinema, we were really exploring the city in a way that we were looking for wilderness experiences within the urban experience, instead of imagining you had to go somewhere to get nature to receive nature within the city. Not just external nature, your own nature, through exploration. So it was a way of kind of feeling body contact with actual space, which for me, it was all about generating meaning and belonging, and not just being a pedestrian being insubordinate to our expected ways in which we move in the city as civilians.

Kerrie Burke-Avery 03:17

So I’m Kerrie, I work for a company called Bricks, and we’ll be working with the developers on site. So part of the planning application asked for a condition for the site to work with the local communities to develop a piece of public art. So an art being a kind of like a big formal word. But actually, what we wanted to do is create an engagement programme so that the new residents could meet some of the older residents that lived around here for ages and also learn a bit more about the site, and what’s important about the land that the houses have been built on. So we’ve been working with Kayle, to develop a series of community workshops. And the end one will be an installation of a food map, which will probably go somewhere around here, which will show all the different foods and things that could be foraged in the area and used in the area. And so our first workshop was looking at examining what was in the area so you can create this map, and some of you are here for that. And working out, we’re going to also plant some trees at the final event. This one is now looking at more sort of medicinal side of things and looking at the way that herbs can be used or different materials in the area can be used. So really celebrating what used to be on the site and what’s around the site and will stay around the site for years to come.

Kayle Brandon 04:35

Heath Bunting and I started a map of Bristol in 2003. And we started mapping the city in terms of the edible plants growing in the city. And we also plotted plants, trees bushes that were rooted in private spaces, but we’re branching into public space. So it was also a dialogue around that. And also the map didn’t have road names. So it was actually like, actually looked like a leaf skeletal structure or something. And it was kind of mind boggling to kind of, kind of look at the map, but it made you kind of imagine the city in a different way. And this was way before Google Maps. And it was a way of repositioning kind of plant, plant persons, I should could say that in a way that kind of changed the composition and made it more clear that you know, they, they’re here and here before and here after us, you know.

Teresa Hazelwood 05:50

So hello, yes. I’m Teresa Hazelwood, I’m a landscape architect. I’m the landscape design director at Pegasus group. I look after the landscape design side of things. So we regularly work on large scale housing developments and designing or the green infrastructure for them. Pegasus as a company specialises in master planning and landscape design. So yeah, things that can compromise diversity are a variety of factors: cost. So cost for implementation, costs for ongoing maintenance, might depend who’s maintaining it. Some sites go to local authorities, some sites are looked after by private management companies. So some of the issues might come down to any opinions or restrictions that local authorities may may place on some of the designs. And theres things like the aesthetics. I think developers can often want sort of neater, more well presented sites, especially during obviously the sales period. And having a nice you know, manicured shop frontage. Versus obviously, ecologically sites can look a little bit more unkempt, or certainly at certain times a year. So the two don’t always go hand in hand. And then there’s the can also be kind of a conflict over sort of like the use of the open spaces, especially on small sites where you’re trying to balance potential requirements for play provision, for open, sustainable open draining systems, for highways, for parking. So I think sometimes the diversity or having some, you know, decent size open spaces given over to wildflower meadows, and things can come quite a long way down that list. So it’s not always as easy to marry them all together.

Kayle Brandon 07:34

Driving out to that site, the Stoke Gifford site, obviously one of the first things you see at the moment, which is going to change rapidly, is those huge mounds of earth, that have all been dug up ready to kind of flatten for houses to go on top of and concrete and all the different materials we use for housing developments. And the earth just looks so good, it just looks so rich and full of lovely minerals. And it makes me feel a bit sad, actually. And in terms of how the site and in relation to how people experience the nature of that, I think it’s, it’s clearly going to be mostly built on, and building practices, the way they’re currently looking, don’t really acknowledge the Earth that the materials that the houses and the roads go on top of. Or acknowledge the need, and necessity, absolute necessity, for spaces that aren’t just human facing. But in relation to when you meet the community, and how people want to make homes and neighbourhoods and have spaces for children to feel safe and, and nice walks and things like that. And Engie, the commissioners, obviously they’ve kind of recognised the importance of cultural practices within building communities and kind of instigating sites and also environmental needs of houses to be energy efficient and stuff, but I still feel as if plants are marginalised and the needs of non human persons are marginalised within the city and until that changes, I don’t think we really get it. We don’t really get what we need. Great. And Lily, because obviously you’re, how old are you? 12? 14 oh sorry. So yeah, what do you think, like what would you hope to see like, can you imagine you know, when you’re in your 30s what kind of environment would you like to be living in?

Lily 09:58

I’d hope that there was more greenery around and like, more different flowers that people could see that you wouldn’t normally see on a daily basis maybe, or trees, that maybe you could go and see, and maybe people could talk about them let people know what they are. And that people could be in the environment where, like, it’s not full of houses, and that is somewhere almost to get away from like every day, and it was just a bit more like calming.

Kayle Brandon 10:31

I think it definitely is a tool for activism, it’s almost like a quite a call to arms. But in a very sort of gentle way. You know, it’s sort of, like, you know, calling it you know, your plant neighbours is to say, you know, these plants are your neighbours as well. And to also reference, you know, may the many blossom and bloom, you know, may the many flower and flower, you know, like, it’s like, not just us, you know, anymore, this is about everybody. And everybody’s not just humans, when we’re talking about a city. Brass rubbing, it has got this lovely printing ability to kind of distribute information. So it kind of speaks of early activist, kind of printing presses in some ways where information is being kind of printed and sent out. And I really liked that, you know, because it has that ability to distribute information, but in this kind of, really, kind of physical analogue way, you know. And yeah, I love the kind of open source aspect of it, and how it references all those kinds of approaches. Yeah, at the event on on Saturday, I just love to how people delighted in the rubbing, and like, it seemed like kind of, like, you know, early forms of magic, everybody who did it was just like, oh, wow, you know, this is revealing itself upon the paper. And, yeah, that just, that just brightens my day every time you know, so nice. Okay, do you want to do a large one, you can take a whole one home?

12:08

Can I really?

Kayle Brandon 12:09

Yeah of course, yeah

Riah King-Wall 12:10

It’s so beautiful, the whole thing.

Participant 12:14

Yes, well I liked yours.

Kayle Brandon 12:18

I’m gonna have to hold them down because they’re…it is like magic, isn’t it? I think it’s really valuable to have workshops on the process of making. And in some ways, some of these projects, it’s a shame we just can’t go on for a good year, you know, like, actually, the length of time it really takes to build relationships for community projects is it’s quite, it’s often the main work isn’t it, of community, social, public art projects. So having the workshops as a lead in was really good as a way of getting to know the site obviously, I didn’t know that so I don’t live there. And you know, often it sort of like, you know, not imposing yourself as an artist is really important, you know, like to get to know the site, to get to know the place and get to know people is pretty much one of the core of the works, you know? So the first one was with herbalist Chris Roe and the second one as well with Chris was was with Chris Roe, he’s a Bristol based herbalist who has his apothecary at Grow Wilder. And so we carried out the workshops together. So the first one we went on this sort of walk, we went on a walk and we sort of looked around at the different plants in the area, talking about the herbal and edible benefits of them. And everybody was really interested and it was really nice. It was blackberries season, so we ate some blackberries along the way. There was still a few cherry plums hanging around… There’s a few more blackberries over there, but they’re quite hard.

Participant 14:56

There’s a ledge just further on, up the road on the right hand side or next

14:59

There’s quite a lot 10 yards down there as well.

Kayle Brandon 15:04

All right, let’s get some more blackberries and then we’ll go back The next workshop was around about the time of the elderberries coming out. So we decided to focus on making an elder syrup, which is really really good, like immune boosting tonic syrup for this time of year. So that’s another thing about just going back to your previous question around kind of how people consume food through supermarkets or consume foods through seasonal produce that’s available. When you understand that different, that different foods come in different seasons, you can see how they relate to the needs, like actual your own needs as well, you know, but that the elderberry come out the time when people need to start boosting immune systems. It’s amazing, isn’t it?

15:09

Oh is that nice, or is it a bit bitter?

Kayle Brandon 15:25

First of all, we need to find out how much we’ve got.

Chris Roe 16:00

So yeah, we need to strip the fruit off the berries. Which will be a messy business. So we can do that. And then, then we’ll work out how much sugar we need. Yeah, I think probably what we’re doing is…

Kayle Brandon 16:26

We started making this elder syrup, and it was lovely. And we had some really, an interesting participant came along, who was from a Romany background and had these amazing recipes that had been passed down through her family line on like really good immune boosting, recipes, things you do when you need when you’ve got a cold things, you know, like it was, so that was really fascinating. So then we started all sharing that different kind of experience of herbal and local remedies for things like that. Chris and I had started gathering like elderberry before because we knew that that site didn’t have many trees. Actually, there are a few elder trees in that area. But they all seem to have been, some of them seem to have been kind of cut down, which, according to traditional folklore is not a good idea. I just thought we would have a brief stand around this elder because it’s the local elder. And it’s one of the only elder trees in the area. It must have been cut down and it must have been quite a big tree. Because I can see that there’s a stump down there. And it’s managed to kind of, it’s growing it shoots out again and turning. So yeah, I just thought it’d be nice to sort of have a look at this one and say hello to it.

Participant 17:58

So does an elder normally, is it just like a normal tree with one tree trunk that grows up? Because obviously this one’s…

Kayle Brandon 18:04

Yeah, so this one’s been this one would have been cut down and it’s returning after being cut. In folklore, they’re really related to magic and it said that the crone aspect of the triple headed goddess lives within the elder and apparently it’s really bad luck if you use elder selfishly. The elder mother can then kind of use her magic powers to kind of tell you off for that. I love the kind of, how both the brass plate and the cyanotype and the and the elderberry making are all about chance forming kind of materials or like experiencing the kind of magic of you know, of making with nature. When I first went to the Roseneath site, the landscapers and planting commissioners, quite often these places use really generic plants. That kind of don’t, yeah, loads of them are just really the intention is oh, it’s hardy, it will last, it won’t shed too many leaves, it won’t be inconvenient, it won’t, it won’t spread out, it won’t impinge, it won’t, you know like basically quite a lot of the planting choices are about that. Oh, it won’t fruit so there won’t be mess on the floor, etc etc. So I thought considering we were doing like an edible food map that we needed to kind of acknowledge that, that to have kind of plants that do fruit or not, produce berries create shade, grow, multiply, provide food for non humans as well, was a good thing. And that, actually, we need to see more of that.

Teresa Hazelwood 20:15

What do I hope for green spaces within high intensity housing areas? Well, I guess it’s for them to become really well used and valued open spaces for the new communities. And for those spaces themselves to kind of help encourage that sense of community, bring people together, so that they become valued and well cared for. And that they are either extensions of people’s own gardens or for them that maybe don’t have their own open spaces that they very much feel that they are they’re spaces that they can, they can go and use. You do see some of these community initiatives where they start to turn some of these spaces into edible landscapes or start to put their own raised beds in and take that sense of ownership and really start interacting with the space and and yeah, almost using the initial designs as a starting point, but you know, they grow it grow into it, make it their own, I think is eah, would be something that’s really nice to see and probably doesn’t happen happen enough.

Kayle Brandon 21:08

I saw people kind of meeting and connecting and, and forging new relationships through the Roseneath project, that was really good.

Teresa Hazelwood 21:19

What you’ve produced for this site sounds personally really interesting. I have an allotment, I’m interested in, you know, food production and engaging with edible landscapes and things and I can’t help but think on some of our much bigger developments, you know, where we’ve got several 100 houses, we’ve got a huge amount of public open space and we’re designing things like community orchards into those spaces, and we’ve got allotments and all that sort of stuff actually kind of having this kind of interpretation strategy, almost, you know, that there is almost like this foraging route around some of the sites would be really quite a nice layer to kind of add in to, to the development,

Kayle Brandon 21:54

I suppose with with making the edible map of Roseneath area, what was lovely was about meeting the people who came and who were related to that place and or who were newly arrived to that area. And I suppose one thing is to start those conversations, and to start kind of inviting people to make more responses and works about it. Yeah, you know, arts practice is a great space for it. And just need to plant more trees. Lately, I’ve been listening to this song by Moondog and I really like it because the song’s called ‘enough about human rights’. And, obviously, I totally believe human rights are really important. However, he goes through lots of different non human entities and the song ends with what about plant rights…

recording of Moondog plays 22:56

Rowan Bishop 23:25

Thanks for listening, we’re Bricks, a social enterprise with the mission to support creative communities in Bristol, helping them to thrive. We work with communities, developers and local artists to produce programmes that support both local voices and Bristol’s creative economy. In 2021, we delivered public art projects across a range of developments from hotels to new housing, neighbourhoods, schools, and listed community buildings. If you’d like to get in touch, learn more about Bricks public art producing or find out more about the art work discussed in this podcast please visit bricksbristol.org and follow us for updates on all the usual social channels. To be the first to hear when we release new podcast episodes, be sure to subscribe to our feed. And if you enjoyed this episode, feel free to leave us a review. This podcast was produced by Rowan Bishop. The Roseneath Gardens public art project was commissioned by Clarion Housing Group with support from Engie. Thanks also to South Gloucestershire Council.

END OF TRANSCRIPT.